Prokofiev, Bartok Interviews

(Via Jessica Duchen, British music writer and Korngold biographer.)

In this 1944 radio interview in English, Bela Bartok discusses the pieces in an upcoming recital by his wife. At this time, he was suffering from leukemia and had a little over a year to live. Bartok’s English is fluent, but his accent charmingly has a little Peter Lorre flavor (make that “Peter Lorre impersonator” flavor, since the real Lorre had an additional Viennese sound that Mel Blanc et al. missed.) Bartok speaks in some detail about forms and folk influences of these pieces.

And here’s a short video of Sergei Prokofiev playing the piano and talking about what he’s composing. The excerpt is from Scene 5 of his opera War and Peace, which had just had a partial concert performance in Leningrad. At that moment (the middle section of the waltz), Anatole Kuragin has been going after the engage Natasha, and he gets her alone to kiss her and hand her a love letter. The entire scene IS the waltz, except for Natasha’s interjections in her own musical style, which wane in strength as the scene goes on.

(Via Jessica Duchen, British music writer and Korngold biographer.)

In this 1944 radio interview in English, Bela Bartok discusses the pieces in an upcoming recital by his wife. At this time, he was suffering from leukemia and had a little over a year to live. Bartok’s English is fluent, but his accent charmingly has a little Peter Lorre flavor (make that “Peter Lorre impersonator” flavor, since the real Lorre had an additional Viennese sound that Mel Blanc et al. missed.) Bartok speaks in some detail about forms and folk influences of these pieces.

And here’s a short video of Sergei Prokofiev playing the piano and talking about what he’s composing. The excerpt is from Scene 5 of his opera War and Peace, which had just had a partial concert performance in Leningrad. At that moment (the middle section of the waltz), Anatole Kuragin has been going after the engage Natasha, and he gets her alone to kiss her and hand her a love letter. The entire scene IS the waltz, except for Natasha’s interjections in her own musical style, which wane in strength as the scene goes on.

Courtesy of YouTube member bramley88: Prokofiev is asked: “Sergei Sergeevich, maybe you will tell our viewers about your work?”

He replies: “Well, right now I am working on a symphonic suite of waltzes, which will include three waltzes from Cinderella, two waltzes from the War and Peace, and one waltz from the movie score “Lermontov.” [War and Peace] has just been brilliantly produced in Leningrad, where the composer Cheshko (?) made an especially noteworthy appearance as a tenor, giving a superb performance in the role of Pierre Bezukhoff. Besides this suite, I am working on a sonata for violin and piano [no.1 in f minor], upon completion of which I will resume work on the sixth symphony, which I had started last year. I have just completed three suites from the Cinderella ballet and I am now turning the score over to copyists for writing the parts, so that most likely the suites will already be performed at the beginning of the fall season.”

The scene Prokofiev plays above is very astutely directed in this DVD by Francesca Zembello:

Prokofiev - War and Peace / Bertini, Gunn, Kit, Mamsirova, Gouriakova, Brubaker, Paris Opera starring Olga Gouriakova, Nathan Gunn, Robert Brubaker, Anatoli Kocherga, Yelena Obraztsova

Twenty Comments on Prokofiev's Piano Sonatas, Part 2

11. The electrifying nature of the principal subject of the first movement of the Sixth Sonata is not founded on its dissonance but on its consonance. In fact, the primary dissonant elements, the alteration between A major and a minor and the leading tone to the dominant, d#, serve to enhance the stability of A as the tonic, they create a stasis, a stability, not chromatic flux, which gives the music its massive bulldozer effect. Paradoxically, it is typical of Prokofieven dissonance that his “wrong notes” and mercurial modulatory schemes achieve centrality rather than tonal diffusion. Consider also Peter’s principal theme in “Peter and the Wolf”…what could be more C-majorish, despite the theme’s flattened mediant excursions?

11. The electrifying nature of the principal subject of the first movement of the Sixth Sonata is not founded on its dissonance but on its consonance. In fact, the primary dissonant elements, the alteration between A major and a minor and the leading tone to the dominant, d#, serve to enhance the stability of A as the tonic, they create a stasis, a stability, not chromatic flux, which gives the music its massive bulldozer effect. Paradoxically, it is typical of Prokofieven dissonance that his “wrong notes” and mercurial modulatory schemes achieve centrality rather than tonal diffusion. Consider also Peter’s principal theme in “Peter and the Wolf”…what could be more C-majorish, despite the theme’s flattened mediant excursions?

12. The finale of the Sixth finds its analogy in the tarantella of death from Schubert’s c minor sonata. Prokofiev even includes the haunting seductions of the Erl-king, marked “dolcissimo”, naturally. Especially ominous is the casual integration of the first movement’s dissonant d#.

13. The Seventh sonata’s sequence of invention, waltz, and toccata gives the work a strikingly heteregenous, dislocated character, enhanced by the bizarre tonal juxtapositon of B-flat with its tritone, E, for the central panel. The evocation of Bach and then Tchaikovsky in the first two movements bring Prokofiev’s use of antecedents close to Stravinsky, and except for the blunt bombast of the sonatas’s conclusion, the piece really feels close to neoclassical Stravinsky in its alteration of the dry and the saccharine.

14. Prokofiev’s formal strategies are exceedingly traditional, as Richard Taruskin points out, but they also show tremendous erudition. The first movement of the Eighth finds its analogy in Beethoven’s alternating bagatelle sequence in his “sonata quasi una fantasia” op. 27, nr. 1. The scheme in the Eighth’s first movement may also call to mind Shostakovich (7th and 8th symphonies) in its yoking of reasonably placid lyricism with disruptive violence. Bugle calls animate the movement with a kindred irony to Shostakovich. Sonatas 6-8 are Proko’s so-called “war” sonatas, which invites an interesting comparison with Shosty’s “war” symphonies. Prokofiev was the greater melodist, but he lacked Shostakovich’s mastery in calibrating long continuous structures.

15. The Eighth is the greatest of the sonatas, not least because it requires everything from the player. Virtuosity, stamina, lyricism, and especially, a gift for almost endless dynamic nuance. The dynamic athleticism of Bartok and the subtle intricacy of Chopin are equally necessary. In fact, the slow movement of the Eighth is marked “dreamily” and is in Chopin’s preferred key of D-flat major, inviting an approach to the piece as a nocturne. And as for use of both pedals? Few works require the imagination required in the Eighth.

16. The Ninth is a throwback to the domestic sonata. After the “war” sonatas, I’m reminded of the biblical line, “Lord, in thy wrath, remember mercy.”

17. Is it weird that he dedicated the Ninth, easily his easiest sonata since the First to Sviataslav Richter, the great virtuoso? Richter loved it. As mentioned in part 1 of this essay, the C major is iconic, in a Beethovenian sort of way. Prokofiev was obsessed with C major; is this an atavism?

18. The Ninth sums up elements from the earlier sonatas, such as a return to the bagatelle conception learned from Beethoven and exploited in the Eighth, which is revisited in the slow movement of the Ninth. It also lovingly invokes one of Prokofiev’s most effective tropes, the evocation of childhood, as well as the evocation of the sort of limited technical means in music for children. Like Mussorgsky, there is both dignity and affection in Proko’s music for children.

19. As a whole, the greatest achievement in these sonatas is the inventiveness of the textures. Prokofiev becomes a sort of latter day Liszt in his constant re-invention of piano sonority.

20. Unlike Scriabin or Medtner, whose mature sonatas, while excellent, are too harmonically and texturally similar, one from the other, or the piano sonatas of Rachmaninov, whose two excursions into the genre are too conditioned by the Romantic school, Prokofiev’s sonatas provide a special comprehensiveness of his style, and are thereby especially rewarding when presented as a cycle.

Twenty Comments on Prokofiev's Piano Sonatas, Part 1

Read Part 2

1. The cycle begins and ends with Beethoven: The cycle begins in stormy f minor and and concludes in luminous C major. Even the look on the respective pages is similar; compare the chords and arpeggios at the beginning of Prokofiev’s First with the chords and arpeggios at the beginning of the finale of Beethoven’s op. 2, Nr. 1, and compare the ethereal doodlings at the end of Prokofiev’s Ninth and Beethoven’s op. 111. I don’t believe this to be co-incidental; recall that Prokofiev pitches his op. 131 in c-# minor, he modeled his first string quartet after Beethoven, and I also suspect that Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony lies behind the stylistic posture of Prokofiev’s “Classical” symphony in specific ways. Further, Prokofiev’s sonata oeuvre resembles Beethoven’s in that both cycles provide a comprehensive overview of each composer’s stylistic evolution.

2. The First and Third sonatas are not formally similar. It doesn’t matter that they both are orthodox sonata forms with lyrical counter-themes in the relative majors and share a tempestuous quality. The First doesn’t stand on its own, it needs other movements, which, in fact, it originally had, but which were subsequently excised. The Third is perfectly proportioned, with sufficient contrast and a satisfying design. By the way, the First Sonata is easy and fun to play, totally comfortable under the fingers, and is delightful in that is sounds harder than it is. Unfortunately, it is not distinguished music. But it is a great piece for precocious young persons to play at studio recitals. That’s worth something.

3. The second sonata is incredibly uneven. On the down side, the thematic material is totally mediocre, the transitions are amateurishly abrupt, and the piece is a hodgepodge of diverse and sometimes irreconcilable styles ranging from Haydn to Schumann to Tchaikovsky and even Rachmaninov. On the plus side, it’s pithy, and has one of Proko’s characteristic scherzos, and a texturally characteristic slow movement. We’re all formalists and “completists” in the classical music world, alas, otherwise, the middle movements could be profitably programmed as separable pieces, like opp. 2, 3, 4 and 12.

4. The Third Sonata is quite viable, but it too has at least two disfiguring blunders. The absurdly amateurish simple chromatic scale introducing the lovely second subject and the tacky tattoo on the neopolitan right before the final a minor chord. That’s a pathetic, tasteless and utterly formulaic cadence. In general, Prokofiev has way too many cadences. Look at the “Classical” symphony; look at “The Prodigal Son” (both ballet and symphony). And another thing: if nothing interesting in this piece happens harmonically, and nothing does, why write in a sonata form predicated on harmonic tension? But the piece succeeds admirably despite these flaws, and that’s because Prokofiev, like Liszt, was an absolute genius when it comes to keyboard texture. He always can find a new kind of exhilarating toccata or splendid two-part invention texture. Also, he knows how to gauge a climax, like Rachmaninov. And he knows how to be lyrical without being sentimental. And he knows the meaning of the phrase, “Do the cooking or keep out of the kitchen”… Prokofiev, as hard a worker on his own terms as even Haydn or Bach, provides good, great, mediocre and bad pieces, but he doesn’t provide boring ones.

5. It’s ten for one and one for ten. But not two for two. Passage after passage in Prokofiev requires individual and imaginative manual choreography. Unlike Mozart, for example, there is a relative paucity of obvious melody/accompaniment patterns. You can think of your ten fingers as ten individuals, and you can think of your fingers as one mega-unit, but if you think about roles of right and left hands in conventional terms, you’re gonna find Prokofiev endlessly frustrating. There’s tons of cross-hand - that’s where my self-ballyhooed new diet comes in handy. There’s less of an impediment to the thoroughfare!

p.s. I’m not joking. Virtuoso music requires you to be in tolerably good shape.

6. With the Fourth Sonata, we come to the first masterpiece of the series. It’s not popular, I understand. Because it’s predominantly slow, and frequently gloomy. Well boo-hoo-hoo, I’m crying. That mean old Russky won’t accommodate my video game attention span. Wake up, pianists. This intelligent, superbly crafted and eloquent work deserves your attention. Richter knew this, at least.

7. If the sonatas were political candidates, the third sells its candidacy with charisma, the fifth with its character, but the fourth deals with the issues. It doesn’t pander, and employs something suspiciously close to logic in its rhetoric and thematic manipulation. Go ahead and make my day by pointing out that the first movement sounds like a Medtner piece as imagined by Miaskovsky, or that the third movement might as well have been written by Kabalevsky. Everything sounds like something else. I mean, doesn’t Olivia Newton-John sound like late Beethoven?

8. Critics howl all the time that Prokofiev writes piano music for the orchestra. This is only occasionally true, and it’s also true that Prokofiev sometimes mishandles the orchestra in ways that have nothing whatsoever to do with his being a pianist. And it’s also true that he sometimes orchestrates magnificently. But the sonatas show that Prokofiev frequently adapts orchestral sounds and techniques to the piano. Listen to the beginning of the Fourth, do you hear a bass clarinet? And how about the bassoons at the beginning of the second movement, or the shimmering flutes and string harmonics in the c major portion of the recapitulation? Except for the First Sonata, which resolutely offers traditional piano style, all the sonatas offer orchestral imagination, especially the Fourth and the Seventh. My goodness, Prok marks “quasi timpani” in the latter work.

9. Forget the irrelevant revision of the Fifth sonata and go for the real McCoy, the original version. Like Hindemith and Schumann, Prokofiev’s revisions tend to be bad because they tamp and inhibit the wild imagination of the original. Vital works become boring. This is true of “The Gambler” and the Fourth Symphony as well. Rachmaninov is the opposite, by the way. His revisions help the team, especially the First Piano Concerto. The cool thing about the original Fifth sonata is that it is a collision between Stravinskyite neo-classicism and Scythian violence. The Soviet revision is la-di-da Soviet pap with a wholly incongruent climax.

10. The revision of the Fifth is rendered irrelevant by the majesty of the Ninth Sonata, which is the apogee of Prokofiev’s so-called “white-note” style.

Read Part 2

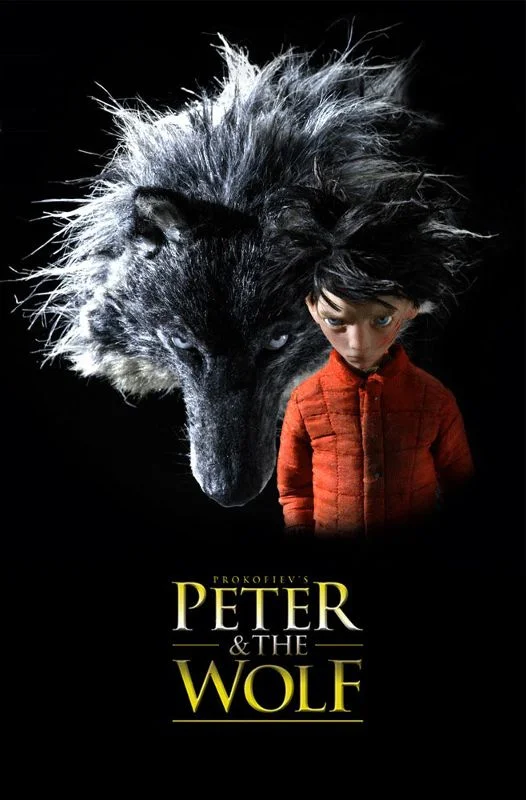

Peter and the Wolf Nominated for Animated Short Film Oscar

Poster from Suzy Templaton’s animated short film of Peter and the Wolf, based on the musical work by Sergei Prokofiev.

One of the world’s greatest film composers may be about to win an Oscar – 70 years after he wrote the music, and 53 years after his death. Suzie Templeton’s stop-motion retelling of Peter and the Wolf, Sergei Prokofiev’s 1936 “symphonic fairy tale for children,” is nominated for tonight’s Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film.

A longer, grittier Peter and the Wolf

As generations of Peter’s fans expect, specific musical instruments represent characters in the story. But Templeton dispenses with Prokofiev’s narrator and tells the story with music and imagery alone — this time, in a modern-day urban locale rather than the canonical bucolic setting. Another departure from tradition: Templeton interrupts the music with long periods of unscored action. These mostly-silent interludes bring the film’s running time to 29 minutes, twice the length of a the original concert work (and Disney’s 1946 animated classic).

Watch the Oscar-nominated animated short film Peter and the Wolf

Prokofiev’s story of one naughty kid who gloriously “gets away with it” is one of his most enduring works — in its original form and in several adaptations and parodies.

Notable Narrators of Peter and the Wolf

A very incomplete list of English-language narrators on recorded performances includes Leonard Bernstein, David Bowie, Sean Connery, John De Lancy (Q!), Dom DeLuise, Dame Edna, Jose Ferrer, Jon Gielgud, Hermione Gingold, Alec Guinness, Melissa Joan Hart (Clarissa), Boris Karloff (Grinch!), Bob Keeshan (Captain Kangaroo), Christopher Lee, Jack Lemmon, Sophia Loren, Dudley Moore, Itzhak Perlman, André Previn, Ralph Richardson, Patrick Stewart, and Sting. Sterling Holloway and Paige O’Hara (as Belle) narrated different editions of the Disney adaptation.

Prokofiev family members have lent their vocal talents to English recordings. The composer’s first wife, mezzo-soprano Lina Prokofieva (credited as Lina Prokofiev) narrates the Chandos / Neemi Jarvi recording. Son Oleg Prokofiev (a sculptor) & grandson Gabriel Prokofiev (an actor and musician) collaborate on the Hyperion recording under Ronald Corp’s baton.

Look who’s lent their vocal talents to Peter and the Wolf!

Listen for free, narrated by

Adaptations and Parodies of Peter and the Wolf

Comedic retellings of Peter and the Wolf have been crafted by Peter Shickele (“Sneeky Pete and the Wolf”), Weird Al Yankovic, and NPR’s “All Things Considered” (in a developing news treatment a la “You Are There”). American holiday movie fans will recognize the wolf’s brass theme as the leitmotiv for schoolyard bully Scut Farkus in “A Christmas Story.”

In the tradition of Wicked (the book and musical defending the witches’ side of the Wizard of Oz story), Peter and the Wolf has even been retold from the wolf’s point of view in The Wolf and Peter by Jean-Pascal Beintus (narrated by Bill Clinton on the Russian National Orchestra’s Peter and the Wolf/Wolf Tracks album).

Updated Monday 7:23 AM: And the Oscar goes to Peter and the Wolf!

Hope You Didn't Miss This

prokofiev-photo.jpg

Several comments on yesterday’s Met Opera broadcast of Prokofiev’s War and Peace:

For those who don’t know the opera, it consists of an epigraph and thirteen reasonably lengthy scenes divided into two gargantuan segments, “peace”, and then “war” based on Tolstoy’s novel. The “peace” segment vitally draws the personalities and ambitions and situations of the principal characters with consummate skill and sympathy, thus making their various fates in the “war” segment deeply involving for the listener. The piece is patriotic, but movingly so; neither obnoxious in the Soviet style nor witlessly jingoistic. Stylistically, the piece inhabits a similar world as the ballet Romeo and Juliet and the music for the film (also turned into a cantata) Alexander Nevsky. In fact, if you don’t know the opera, you might imagine a sort of cross between those works; eloquent dance elements as well as massive and powerful episodes..and like those works, a serious mein, but leavened with considerable humor. And the libretto, by Prokofiev and his wife, Mira, is a winner…combining grandeur and intimacy. Also, the piece is consistently inspired from beginning to end, there are no longeurs…to yesterday’s broadcast:

1. The conductor Valery Gergiev proves once again how important the conductor is…his mastery of the score is immediately evident, and his (relatively) quick pacing and control of tempo, the breadth and unity of conception, the precision of the colors evoked by this onamonapoetic score, and the immense variety of his articulations serve the work well, to say the least.

2. But why the cuts? Oh, I know that everybody but Rostropovich in that Erato record of his makes cuts, and as far as it goes, several performances I’ve heard cut a lot more. But I have the score, and as I followed the performance I can assure you that the music left on the table is not just perfectly viable, but as inspired as the rest. And I’ve heard it uncut, and liked it that way. But Gergiev knows what he’s doing, obviously…there are probably sufficient reasons for the cuts, which in any case were not particularly heavy…You know, I feel the same way about cuts in Frau Ohne Schatten; it’s just about always cut, and when I heard Solti do it from Salzburg uncut, I liked it that way. Guess I just don’t like cuts, I almost always feel cheated. Erich Leinsdorf in one of his books completely dismisses objections to cuts, and claims they are absolutely necessary in many works to make the piece stronger. I just can’t think of any cuts I like in any works I like. Cut away in pieces I don’t like, however; be my guest!

2. If the Met had made this one of their big whoop-de-doos at movie theatres, it would have sold out everywhere and been one of the events of the year. Why didn’t they?

3. Alexej Markov as Andrei and Maria Poplovskaya as Natasha were superlative; especially because their acting and vocal characterizations were so convincing. And it’s nice to have such an Andrei, powerful and charismatic; makes the lyrical stuff all the more moving. The outstanding Kim Begley was wonderful as Pierre, but you might not notice it, ‘cause Pierre is such a difficult role. Sam Ramey as Kutuzov has a beautiful voice and plenty of power, but the wobbling continues to be a significant distraction. A friend I listened with thought it wrecked his passages. I thought so too, but am not saying so because I’ll get yelled at! But Ramey’s place as a great singer of our time is secure, he’s done so many good things.

4. This greatest of Prokofiev’s works contains his single greatest passage, the desperately sad death scene of Andrei… his farewell to the beloved walls of the Kremlin and his hallucinatory reunion with Natasha will shock you with its poignancy… how can this beautiful world continue to exist without Andrei to see it? “The world ends when you die.” This is haunting.

Prokofiev and Berlioz with the Verbier Festival Orchestra

There are an awful lot of good to excellent youth orchestras out there. Abbado has a great one in Europe. Here in Chicago the Civic generally pleases. The Verbiers, from Switzerland, played in Chicago tonight. I was lucky in this concert; as a music teacher and lecturer, I usually have to make my dinner with stale gruel and tepid tap water, but not tonight. A generous patron associated with Verbier’s sponsor, UBS, gave me tickets to the pre-concert reception. Crab legs, salad with walnuts and blue cheese, ravioli suffed with carmelized mushrooms, beef tenderloin with creamy horseradish sauce, and anything you could want to drink…I wanted to miss the Prokofiev and stay with the food. But alas, with polite regrets and best wishes the catering staff shooed me off to the concert. Still, I’m sure my loyal students will continue to come through for me with tickets, books, Cds, etc. You hear that? This means you.

The first half was Martha Argerich and Prokofiev’s Third Concerto. She is a phenomenal pianist, could hardly have done better, but I enjoyed the little Chopin mazurka she played as an encore more than the piece de resistance, although I assure you I liked the tenderloin better than the salad. You know the old maxim about children? They should be seen and not heard. Well, the visual aspect of the pianist attacking and dismembering the piano is better than the aural aspect in this piece. And the orchestration was full of all sorts of miscalculations, the string writing consistently delivering little bang for the buck. All three movements begin promisingly, with Slavic melodies that leave a hint of Rachmaninov in the air. But then you have this deplorable combination of primitivism and neoclassicism. Before anybody gets on my case, I hereby solemnly state that I love many things of Prokofiev; “War and Peace”, the Sixth Symphony, more than half the piano sonatas, and even his other concerti; particularly the magnificent Symphonie-Concertante for cello. Speaking of primitivism, Bartok’s First Concerto fits the bill, and speaking of neoclassism, you could do worse than Bartok’s Second Concerto. I honestly think Prokofiev copies Stravinsky, like he did with his “Scythian Suite”. But whether yea or nay to that, the Third Concerto is all too limited in the type of piano sonority it evokes. Evertything is either a motoric toccata or actual banging, which is exciting but limited. The second mvt., however, has an interesting conceit; alternating violence with Slavic pathos. The Verbiers were outstanding in a reasonably difficult accompanying capacity, and in fact I was especially impressed because accompanying sensitively is a skill that often eludes brash, hot-shot virtuosi.

Berlioz “Fantastique”…here is a work that wholly deserves its canonical status, and is a perfect vehicle for brash, hotshot young virtuosi. They overdid it, I guess, but then,that’s part of the message of the piece. Nothing succeeds like excess. Every single time I hear this incredible piece, I’m struck by its essential modernity and its sense of humor. I’ve made an entry about it which you can access here: (Revenge article). Who else would depict his composition, theory, and I’m almost certain, at least one especially noted Russian music expert (from the Paris Consevatory, of course) as capering demons at a satanic orgy?

I’d like to say something serious about the Berlioz: the slow movement, “Scene in the Country” is the fantastic heart of the work, also the fantastic heartbreak of the work. I don’t have words eloquent enough to describe the shattering sadness of the English Horn’s attempt to start up again the duet with the oboe that begins the movement, and the lack of reply. Duet becomes solo, and only nature answers, malevolently, with the menace of a thunderstorm. This is Berlioz’s great hymn to loneliness. The Shepherd’s pipe is a voice in the void. Goosebumps, goosebumps, goosebumps. What could be more beautiful?

The orchestra, led by Charles Dutoit, generously played encores of the rousing “Farandole” from “L’Arlesienne” of Bizet, and Chabrier’s Espana. The latter piece has a clever ryhthm, but I don’t know…I’m tempted to resume my habitual snobbiness just now, so here I will stop.